I am the migraine, and the migraine is me. This is one part of who I am, though it certainly doesn’t define me.

I was only 14 years old. My first attack frightened me and my family, as we’d had no history of these severe symptoms and we didn’t know what to do with the searing pain, the nausea, and vomiting, or the lack of any obvious path for treatment.

This was 1978; there were no headache specialists, no migraine support groups, no medications specifically designed to treat this disease. In fact, it wasn’t even known yet to be a disease. Most doctors (as did most people) genuinely thought patients were overreacting to a “bad headache.”

I did have persistent, supportive parents, though, who found a neurologist who would see me. At my first appointment, he asked, with my mom in the room, if I wanted her to leave so “I could tell him anything I might not want to talk about around her.” I was incredibly offended, since I shared everything about myself with her and knew already that I didn’t want to share much with him. This was my first but certainly far from my last experience of migraine stigma.

Back only in the late 1970s (and long before), this debilitating disease was thought to be largely psychological. CAT scans, much less MRIs, were not yet available. I went to a chiropractor, and my doctor prescribed some drugs designed for other conditions that were thought to be helpful to some migraine patients. I became a zombie with their side effects. By the time I was a sophomore in high school, in 1979, I had to quit my basketball and volleyball teams, the school play, for which I had earned a lead role, and so much more. These were the beginnings of knowing the sacrifices one makes living with migraine disease.

Of course, we all know the sacrifices are many with migraine. In addition to the headache pounding over my right eye, which worsened if I bent down or moved my neck, I had so many other symptoms of the disease, many of which were not even yet known to be part of it. I needed to try to continue to function normally and did anything/everything to keep myself from ending up in bed with a full-blown attack.

As the years progressed, I ended up with severe endometriosis, requiring a complete hysterectomy when I was 36. When I woke up, I had the worst migraine I’d ever suffered; from that point I shifted from episodic to chronic migraine, and I have never been able to return to episodic status. I was referred to a superb headache specialist, with whom I worked until his retirement in 2016. Fortunately, he stayed current with available treatments and upcoming research. For years I have been going to a weekly physical therapy appointment for work on my neck, have taken all the rescue drugs I have, know to stay hydrated and try to stay on my sleep schedule—but nothing is working. I also regularly see a chiropractor.

A recent migraine left me walking around with tightness around my scalp and my forehead numb (maybe from Botox or just the migraine). The fog left blanks in my speech, with sometimes the wrong word coming out. I stood still for many seconds before coming up with the word “blanket” and then used “plate” for “refrigerator” a couple of hours later.

One day, when the pain was severe, I went to the pharmacy, only to struggle with the technicians about prescriptions—not giving me enough Ubrelvy, being told they had not received authorization from my doctor to refill my Medrol dose pack, pleading with them to let me have enough medication to get through the weekend, all only to walk away from the window with more problems to solve on Monday but no help for the weekend.

As so many of us realize, with many attacks it’s too difficult to concentrate enough to read or watch television. My mood can be all over the place, from depressed, to teary, to rageful. I am exhausted, want relief from pain, and want to feel less lonely in all of it. Despite a very supportive family, a migraine sufferer cannot help but feel alone sometimes. When the attacks are in a bad cycle, my anxiety is much worse; I shake inside myself and am restless, with no way to get away from it.

Those who know me well care for and support me. This is hard on them, too, because when in either a full-blown attack or in a long-term cycle, I am the migraine, and the migraine is me.

I can say it’s only part of me, but it controls everything I do and don’t do. It alters my personality, takes away choices and freedoms, and steals life from me. I’m existing, not living in these times.

How can these changes not dramatically affect my loved ones? I’m not as present in so many ways: I can’t do so many things around the house, I can’t even bend down for any reason (not even to get my dog’s ball for her, and she looks at me with a head tilted, not understanding).

During the bad times, I cannot Zoom with friends, much less go out with them, as I just don’t have the energy or focus for it.

Part of learning tolerance and sometimes even acceptance of our relationship with migraine is coming to realize that living with it requires a lot of work for our medical professionals, but, even more, for us, as we struggle to keep up with appointments to see headache specialists/neurologists for consultations, medications, Botox, nerve blocks, and infusions. Then there are the different combinations of presentative and abortive medications we try until the right mix breaks the cycle or keeps us from moving from episodic to chronic migraine.

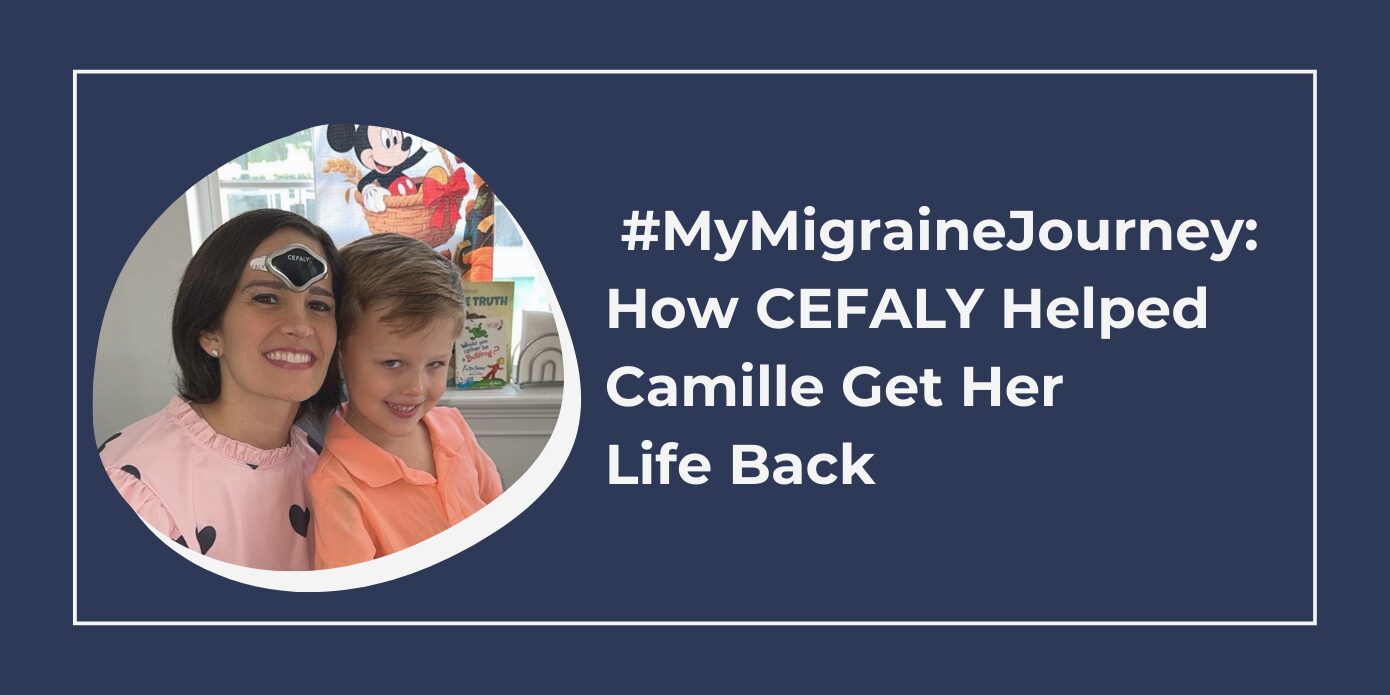

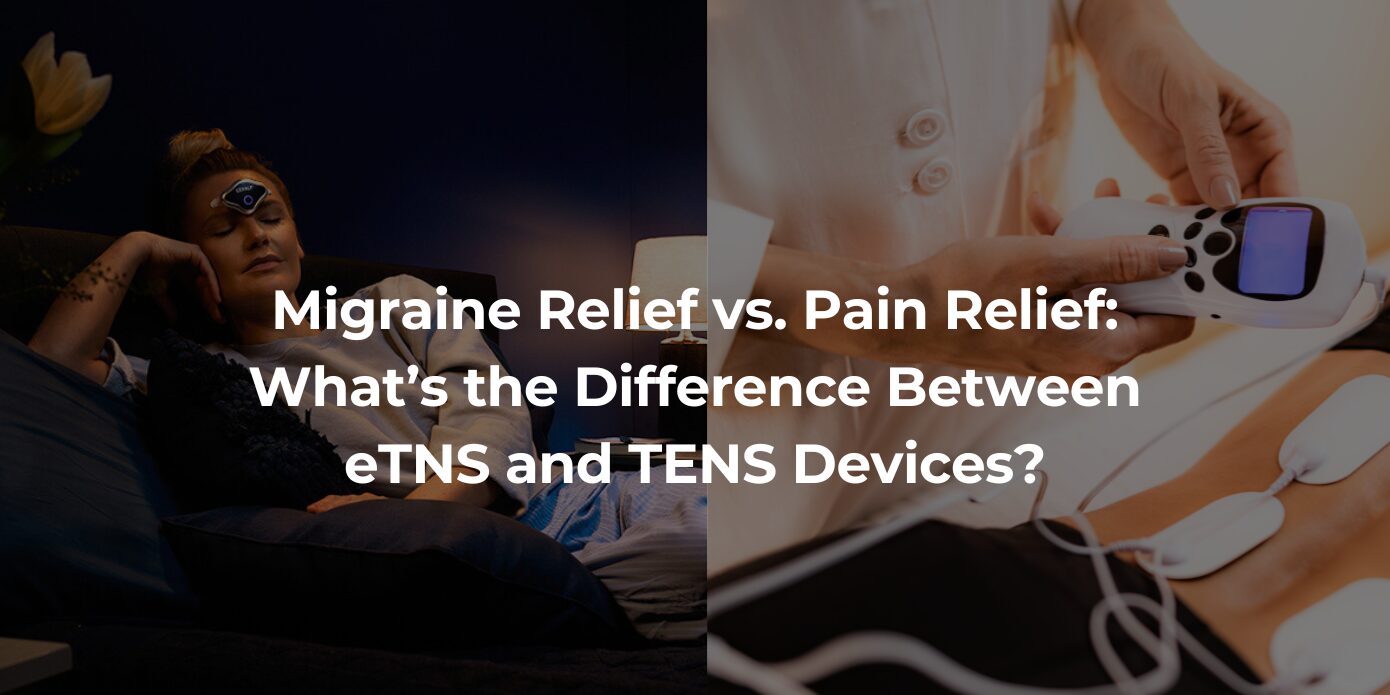

Because I have always been interested in a comprehensive approach to my treatment, as soon as the CEFALY device became available, I purchased the initial unit offered to the public. I used it an hour a day, as I found the increasingly strong electrical impulses comforting and helpful in both preventative and acute treatment.

It’s so important to use complementary and integrative medicines including devices like CEFALY, mind/body treatments such as yoga and mindfulness meditation, manipulation and hands-on treatment by chiropractors and physical therapists, and dietary supplements like magnesium and vitamin B2.

CEFALY has proven to be instrumental in my regular course of treatment. I now have the updated (not yet the newest) device, one that you use differently for preventative and acute/rescue treatment. The good news is that a prescription is no longer necessary, and while the unit may seem like a significant initial investment to some, CEFALY has a fantastic and reliable “return if ineffective” 90-day guarantee. For over 15 years, I have found their customer service to be reliable, responsive, and very personable. Notably, they were founded by migraine sufferers, so they care about their patients.

Only an hour ago, I took out my CEFALY device, cleaned my forehead, applied the adhesive (for me, hypoallergenic) patch, and then the CEFALY. I find great comfort in knowing I’m helping myself, not by just investing in the necessary medicine, but in using the non-invasive treatments, this one in particular for me that can prevent a full-blown attack, keep at bay one that is in the early stages, or entirely abort the attack.

For those of you who follow me through my articles on psychologytoday.com or my Migraine Lit Facebook page, you know I try desperately to promote the benefits of CEFALY; I always have. I do so in my book, So Much More than a Headache: Understanding Migraine through Literature, as well.

We have been blessed with the new CGRP medications, but please know that living with migraine disease takes a team of good medical professionals and a combination of pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical products. Please investigate this fantastic technology, one with no side effects (unless, like me, you apparently have sensitive skin and need their hypoallergenic pads). There’s absolutely no loss, no risk in trying it. Mine goes with me wherever I go; it’s a real gift and comfort.